DOUGLAS TREATY

The following information has been provided by Nick Claxton. (2007)

Beginning in 1850, the Hudson’s Bay Company was appointed authority by the colonial office in London to establish a colony on Vancouver Island. The significance of indigenous peoples relationship to their lands and resources was completely disregarded, and all the newcomers could see was an empty land that harboured boundless wealth for the taking. In the four years following, Douglas completed fourteen purchase agreements with Vancouver Island indigenous nations.

These documents are often referred to as the “Fort Victoria Treaties” or the “Douglas Treaties”. James Douglas did not explicitly use the word treaty in these agreements, but a supreme court decision ruled that these agreements were and remain valid treaties since Douglas who was acting as an agent of the Crown at the time arranged them with the indigenous peoples (Regina V. White and Bob 1965). First Nations argue that their ancestors understood this as a peace treaty and not a purchase agreement. These treaties effectively abolished aboriginal title to those nations that signed them, but promised to allow those indigenous peoples to carry on their fisheries as they formerly had, for millennia. Arguably, for the Saanich peoples and for all indigenous peoples on the pacific slope, their fisheries were, and still are necessary for their existence as independent nations. The Saanich people have never surrendered title to the Gulf Islands and we also feel that our territory expands across the U.S.A. border.

The Northwest coast of what is now called North America has been home to Aboriginal nations for many thousands of years before any European individual has erroneously been able to do the same. White people only began to arrive to the coast of British Columbia in any significant numbers in the 1850s. Many First Nation elders can testify to a time when our Nations were free from any white influence.

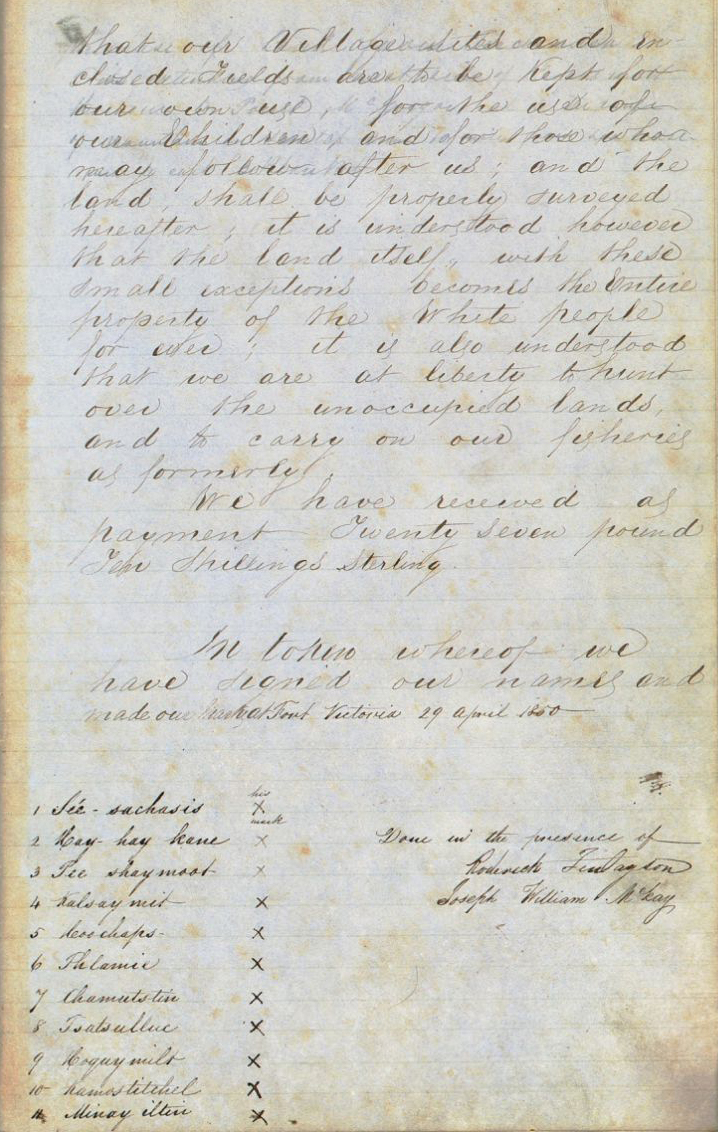

The pages of one of the Douglas treaties, this one covering lands from Esquimalt Harbour to Point Albert along Juan de Fuca Strait.

During the early contact period, the fur trade between aboriginal peoples and Europeans developed without much colonial control. Trading companies established fortified trading posts, but Europeans at this time remained vastly outnumbered. Robin Fisher (1997) in Contact and Conflict contests that during this time control over Indian lands and societies remained in Indian hands. It was not long before the British Crown endeavoured to exercise its sovereignty over indigenous peoples and their lands, which was to become the driving force behind the Douglas Treaties.

Paul Tennant (1990) thoroughly recounts the time preceding and including the signing of the treaties in his book, Aboriginal Peoples and Politics, albeit from a colonial perspective. He states that after the establishment of the colony of Vancouver Island in 1849, the Hudson’s Bay Company had been granted control of land and settlement of the colony. The Company’s chief factor was James Douglas. Regarding the land and colonization of the land, explicit instructions were sent to Douglas from Archibald Barclay in London, who was at the time the company’s secretary. It read:

“With respect to the rights of the natives, you will have to confer with the chiefs of the tribes on that subject, and in your negotiations with them you are to consider the natives as the rightful possessors of such lands only as they are occupied by cultivation, or had houses built on, at the time the island came under the undivided sovereignty of Great Britain in 1846. All other land is to be regarded as waste, applicable for the purposes of colonization. The right of fishing and hunting will be continued to the natives, and when their lands are registered, and they conform to the same conditions with which other settlers are required to comply, they will enjoy the same rights and privileges.”

Indigenous philosophies of land cannot be translated into European philosophies of land. The colonial assumption that the land was waste by simply appearing to be unoccupied was and is completely incongruent to Indigenous principles. Thus the Douglas Treaties not unlike subsequent colonial policy, simply do not suit Indigenous Philosophy, rather it simply but devastatingly serves to disconnect indigenous peoples from the land. There is also the notion that Indigenous peoples will simply be absorbed into the dominant society, to ‘enjoy’ the same rights and privileges as other Canadians, no more. This mentality I would argue is at the root of the present policy of modern day treaty process. The colonial vision of domesticating indigenous peoples and their rights is the main objective of that policy, as it has been throughout the history of Imperial rule in British Columbia.

Paul Tennant (1990) states that Douglas departed slightly from his instructions from England in his negotiations with indigenous peoples. Tennant bases this claim on the wording of the treaties themselves. He argues that Douglas regarded that Indigenous communities owned the whole of their lands within their territories, and that is what he was purchasing on behalf of the Crown, excepting Indigenous village sites and enclosed fields. Although Governor Douglas may have recognized Aboriginal title the whole of an Indigenous communities traditional territory, progressive as it may seem for that time, he still extinguished all of it but to that of the ‘village sites and enclosed fields’. Tenant states that even though these treaties only left a few acres per family, it did leave it under title of the Aboriginal people who signed it. He further justifies Douglas by saying he was more generous in fisheries, acknowledging the unqualified and unlimited right to “carry on our fisheries as formerly”. As mentioned earlier, indigenous fisheries were central to indigenous societies and to their identities as independent nations.

To further confound Douglas’s apparent generosity to Indigenous Communities, James Hendrickson (1988) presents an account of the unusual way the treaty itself was created. Douglas initially had the indigenous leaders of the community sign their ‘approval’ at the bottom of a blank sheet. In search of the appropriate text to complete the document, Douglas used text that was virtually identical, except for the addition of appropriate names and dates, to a treaty signed a decade earlier in New Zealand, the Treaty of Waitangi.

This alludes to another discrepancy ignored by Tennant, whether the indigenous representatives fully understood the implications of signing the treaty. Chris Arnett (1999) speaks to the Saanich situation on that question. Unlike the other agreements, the one made in Saanich was made with the actual text of the deed in place at the time they were signed. However, the oral history of the Saanich states that the leaders “did not know what was said on the paper” (Arnett 1999). Even if there were interpreters available to the Saanich, the promises that their winter villages, food gathering sites, and most importantly their fisheries were to be protected would have led the Saanich leaders to assume no threat in signing an agreement with the newcomers.

Arnett also argues that the indigenous peoples perceived that the agreements were only a confirmation of ownership of village sites, food gathering sites and their fisheries. From an indigenous perspective, entering into agreements with the colonists represented an agreement where indigenous nations and the white people could live side-by-side, together sharing the land. Conversely, it can be alleged that the colonial principles of land ownership and use were imposed on to the indigenous peoples who signed these agreements, and indigenous peoples were to be domesticated into Canada. Despite the apparent deception tactics and imposition of European principles of land ownership, the Douglas Treaties still guaranteed the indigenous fisheries as formerly. This right, I would argue has largely been ignored and infringed upon right up to the present day despite protection of the treaty.